After they took my mother to the funeral home, my brother, his significant other, Susan, and I headed back to the hotel in Delray Beach. It was after ten  o’clock and almost everything was closed. We stumbled into Boston’s near the beach and convinced them to serve us. A live blues band made it hard to be heard, but we found an almost quiet table on the street. I realized I was in shock. Less than four hours earlier I held my mother and checked her pulse and felt it slowing until it was no longer discernible. Now I was in a bar-restaurant eating a Caesar with chicken. I felt alternately guilty and relieved. It was over, but I really didn’t want it to be over. When I sat next to her as she lay dying I begged for a do-over. Let her gasp, open her eyes, and be back with us, if only for a few more weeks. I thought I was ready for her to pass, but I wasn’t.

o’clock and almost everything was closed. We stumbled into Boston’s near the beach and convinced them to serve us. A live blues band made it hard to be heard, but we found an almost quiet table on the street. I realized I was in shock. Less than four hours earlier I held my mother and checked her pulse and felt it slowing until it was no longer discernible. Now I was in a bar-restaurant eating a Caesar with chicken. I felt alternately guilty and relieved. It was over, but I really didn’t want it to be over. When I sat next to her as she lay dying I begged for a do-over. Let her gasp, open her eyes, and be back with us, if only for a few more weeks. I thought I was ready for her to pass, but I wasn’t.

I’ve lived sixty-six years, and have been party to many passings. I’ve lost great-grandparents, grandparents, a wife, a father, first and second cousins, close friends, great aunts and uncles, aunts and uncles, in-laws and now my mother. I worked for American Ballet Theatre through most of the 1980s and lost many colleagues and friends to AIDS. My first wife,Vanessa, was in the art and design field, and we probably lost a third of the people she worked with to this plague. Robert, who cut her hair on the cheap in his apartment after his day job doing the same at Bergdorf-Goodman, was one of the earliest victims, dying before the disease was officially named AIDS. But none touched me like this, the passing of my mom. I loved Vanessa dearly for twenty-two years, but I had months to grieve with her, and two weeks at the end when she was no longer able to communicate and I would sit by her hospital bed crying into her shoulder. I’ve written about this elsewhere, but a few days before she died, she woke up and told me to “find a good woman and have a good life.” Minutes later she was comatose again.

There was no such moment of sudden clarity and a final, touching exchange with my mother. She had become almost childlike in her final weeks, delivering ‘I love yous’ and kisses, but little content. I never expected the grief to be this visceral. I keep telling myself that I cannot imagine a world without her, and am not even sure what I mean by that. It’s not like we lived on the same block and I saw her every day. I journeyed to Florida perhaps twice a year, and we spoke on the phone, until recently, twice or three times a week. While she was alive I did feel guilty about not seeing her more, and would go through periods of calling more frequently, but life always gets in the way of best intentions. Now that she’s gone forever I feel the pain of her absence so intensely that it’s hard for me to write these words.

There was no such moment of sudden clarity and a final, touching exchange with my mother. She had become almost childlike in her final weeks, delivering ‘I love yous’ and kisses, but little content. I never expected the grief to be this visceral. I keep telling myself that I cannot imagine a world without her, and am not even sure what I mean by that. It’s not like we lived on the same block and I saw her every day. I journeyed to Florida perhaps twice a year, and we spoke on the phone, until recently, twice or three times a week. While she was alive I did feel guilty about not seeing her more, and would go through periods of calling more frequently, but life always gets in the way of best intentions. Now that she’s gone forever I feel the pain of her absence so intensely that it’s hard for me to write these words.

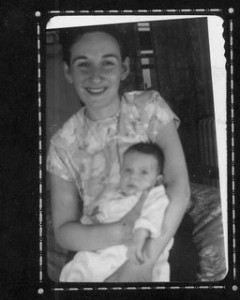

A few hours ago I searched my computer for the photos on this page, and couldn’t hold back my grief. It just came pouring out of me. I saw that beautiful young woman of twenty-four holding her me and cherishing me, and understood that it never changed for her, and there will never be anybody who feels the way she did about me on this earth. Yes, I know I am loved intensely by Wendy and my children and my brother and a few close friends. but it can never be like that; there is nothing in life like a good mother’s unconditional love. I wish I could turn back time and visit her more often, and call her every day if only for a few minutes. Just saying this sends me into a dark despair.

loved intensely by Wendy and my children and my brother and a few close friends. but it can never be like that; there is nothing in life like a good mother’s unconditional love. I wish I could turn back time and visit her more often, and call her every day if only for a few minutes. Just saying this sends me into a dark despair.

As I write this we are four hours short of one week since the moment of her passing and I cannot honestly say my grief has lessened. Grieving for my mother comes in waves. I am now going to do what I tell others to do; go into AfterTalk Private Conversations and write to her, continuing the conversation, continuing the bond.

More to follow