A Son’s Suicide: The Last Person on Earth

by Melissa Fay Greene

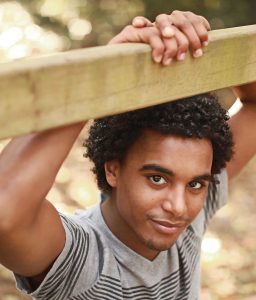

He was a marvelous, graceful boy. We, his lucky family from the moment he arrived at age 10 from Ethiopia, weren’t the only ones to think so. A wide swath of local boyhood fell in love with him, too, migrating to our house, staying off and on, nights and weekends, holidays and road trips … staying, really, until he left us.

His name was Fisseha, American nickname Sol. Before he was even speaking English, in the summer of 2004, he began unwittingly to dazzle us with skills that were second nature to him, a goatherd from sub-Saharan Africa. He could spark fires with sticks and stones, build small huts, and whistle piercingly through his teeth without using his fingers. He harvested wild berries and brought them home in bowls shaped from leaves. He had a gentle knack with animals; on his first walk with the family, he carried home our elderly dachshund as if it were a baby goat at risk of being left  behind in the wilderness. “Very small, Mom,” he explained, seeing my startled expression.

behind in the wilderness. “Very small, Mom,” he explained, seeing my startled expression.

He stripped bark from trees and wove it into twine and then into a sling, a biblical sling. One day, swinging it, he released a pebble too soon and it blew through the Plexiglas basketball backboard like a bullet. The backboard crumpled inward, then rained in pieces onto the driveway. “Mom! Sorry!” he barked with husky, new English. “Can you be careful!” I cried. “You could kill someone with that thing!” With my kitchen knife, he carved a smooth wooden handle for the bullwhip he wove from clothesline rope. It cracked in the air in sharp sonic booms, inspiring males of all ages to jog over to our house to try to learn, usually fruitlessly, how to thwack it.

One afternoon, watching him walk up the street barefoot with a homemade fishing pole over his shoulder, I said to my husband, “I’m not sure, but I think we may have adopted Huckleberry Finn.”

His athleticism became legendary in the leafy Emory University neighborhood. He was the star of every soccer team he joined. Until the final one. But first there was a magical decade of his deliciously excelling at any game or endeavor, including, at home, board games like Risk, Monopoly, and Uno, and somehow there was no one you’d rather be trounced by. On a field of play, he seemed to have an extra gear for speed. By then, he was a teenager with chiseled features and thick curls. When he suddenly accelerated, overtaking his opponents, with his mane of hair streaking behind him, people all around us yelled, “Oh my God, look at that kid run!”

In pickup games with friends (I’d learn later), he occasionally aimed a soccer ball at a weaker player’s foot so that he or she could get the chance to score. I can’t say that I ever saw this. But, in time, I got a couple of letters from mothers whose children had experienced brief stardom following an assist from Sol. He was kind.

He was loving. He was chill. He was happy. And then he went to college. He only went because he wanted to play college soccer. Illiterate till age 10, he was no scholar. We were game. If he wanted to be in college, he’d go to college; if not, a world of possibilities awaited. At the state university he attended, he sat on the bench his freshman year of varsity soccer. This astounded us. Later, in a guest book, one of his high-school coaches would write: “Sol Samuel was the most gifted athlete I ever saw.” But okay, it must be a great team, we thought; they don’t need him yet. Then sophomore year, the fall of 2014, still on the bench, he asked us not to come to the games. What kind of spectacular team is this, we wondered, that has such an incredible roster it doesn’t need Fisseha?

And then he was dead.

First he was “missing.” The coach phoned on Thursday afternoon to say he hadn’t shown up for practice, for the first time ever. My husband and I and Sol’s siblings, teammates, and friends all over the state took off looking for him. I slept over in his college apartment, awake all night, waiting for him to stroll in and laugh with astonishment at all the hoopla. I sat up eagerly at every sound. My main hope was not to scare the daylights out of him: a college sophomore coming home late and discovering his mother in his bed! As the hours passed, his cell phone filled up (we saw much later) with increasingly frantic and loving and insistent texts and calls. The assistant coach sent this snarky comment: “If you quit the team, don’t you think it would have been nice to let us know?” Sol never got any of the messages. The police found him the next day, in a noose woven from clothesline rope, hanging from a tree in the woods above the college soccer fields, wearing his uniform, having left a suicide note about the coach.

It was so impossible, so unthinkable, that even when we sat in the office of the university president on Friday afternoon and were told by the county sheriff that they’d found a body, we scoffed and said it couldn’t be him. Then the sheriff said the coach had identified the body, and for me, at that moment, the air above the sheriff’s head split open, a rent in the fabric of the world as I’d known it.

For our community, it was a shock of Anthony Bourdain–like proportions.

One of his college teammates called me sobbing in the small hours of the next morning and said, “Sol never would have killed himself. I think it was murder. I think someone lynched him.”

“Sweetie,” I said, “who could have caught Sol? Who could have pinned him?”

Crying loudly, he assented and hung up, and I rolled over and kept crying.

Of course no one knows what to say. But I can tell you what not to say.

Don’t ask, for example: “Had he been depressed?”

Don’t ask: “Had he tried it before?”

Don’t write, if you’re a stranger in a distant state who never met him: “Thank God his suffering is at an end.”

Don’t muse: “Weird, they always looked like a happy family. I guess you never know …”

Don’t assume, as we all assume when it happens to someone else: They must have missed red flags. Many people hinted that something had to have happened in Sol’s past, that there was some buried trauma from his early childhood in Ethiopia. The theory was that when the coach, at the Wednesday-night, October 8, 2014, home game, kept him on the bench once again, despite (in Sol’s view) guarantees and promises that he’d play — the repressed trauma broke loose, roared back, and undid him. Well … maybe. I’ve given that one a lot of thought. But, in ten years together, wouldn’t we have seen some trace of it? At least once?

He was still in love with his high-school girlfriend. He was brimming with plans — including a 21st birthday in January, a 2015 spring-break trip to Jamaica with buddies, and a summer trip to Ethiopia for a second return visit to his grandmother and extended birth family.

We’ve had three years and eight months to think about this.

And no one among his family members and friends, and teammates and teachers, and coaches from grade school through high school, including coaches who took him to Israel, Jamaica, and Spain for tournaments — no one among us has been able to come up with a single warning sign. No one could have predicted that this young prince from the Ethiopian highlands would perish in the face of indifferent treatment by his college soccer coach on a nondescript Wednesday night.

It turns out there are a lot of things the general public doesn’t know about suicide. At least I didn’t know them. And learning about three specific aspects has helped me, a little.

The first bit of information arrived a few days after the event, as I staggered in shock through a neighbor’s tangled backyard, sleepless, unable to eat, barely able to swallow. A friend of our middle daughter phoned to say he’d recently learned something about suicide, following the shockingly sudden death of his own close friend. He felt it was important for us to know, in case we didn’t, that there were two types of suicide: the widely known “premeditated” and the lesser-known “impulsive.”

Impulsive suicide can happen without “calls for help,” suicidal ideation, mention of “ending it all,” depression, mental illness, anxiety, social isolation, giving away prized possessions, “getting affairs in order,” or earlier failed attempts.

It can strike like a thunderbolt, out of nowhere.

What did Gladys Bourdain just tell the New York Times? “He is absolutely the last person in the world I would have ever dreamed would do something like this.”

Same here.

Perhaps new revelations will emerge about Chef Bourdain — I never met him, I know nothing about him. But his mother’s sentiment is precisely mine.

Living through this thing resembles, I think, that TV show The Leftovers, where 2 percent of the world’s population simply vanish one day without explanation and there seems to be no meaning behind who disappeared and who remained.

You’d think we’d know more about this kind of suicide. According to studies, between a third and four-fifths of all suicide attempts are impulsive acts. In one survey, 70 percent of people who’d survived near-lethal attempts told researchers they’d acted within one hour of making the decision to kill themselves. Twenty-four percent reported they’d attempted suicide less than five minutes after deciding to do it.

Suicide-prevention strategies are based on the theory that a person first thinks about suicide, then plans it, then attempts it, and that this “template” can take weeks, months, or years to unfold. Interventions can occur at various points along the timeline, beginning with the identification of an “at-risk individual” whose progression from one stage to the next you try to interrupt. But people who act impulsively blow past the timeline. The Centers for Disease Control recently reported that suicide rates have risen in nearly every state and that “more than half of people who died by suicide did not have a known mental health condition.” Scientists hope that, in time, a set of red flags will be identified for this different sort of at-risk population. But, for now, there aren’t any.

“Suicide almost always raises anguished questions among family members and friends left behind: What did I miss? What could I have done?” writes Patrick J. Skerrett for the Harvard Health blog. “But when individuals suddenly take their own lives with no warning, all we can do is look to each other for support. It may be natural to ask, ‘What did I miss?’ But we should remind ourselves what experts say: This kind of death defies prediction.”

On the last morning of his life, a huge risk factor appeared: Sol started drinking. He was a nondrinker, an athlete. But he obtained a fifth of vodka, downed as much as he could stomach, and was practically falling-down drunk when he got the rope out of his car trunk and walked into the woods. The second fact I learned about suicide is that about a third of people who kill themselves used alcohol just prior. If Sol had been at home or among friends when he started guzzling vodka on a Thursday morning, of course we’d have intervened! But he drank alone in his apartment. Only the police blood-test results and the empty bottle on the forest floor told the tale.

The third bit of information I learned about suicide is anecdotal rather than epidemiological or statistical, because the numbers involved are minuscule.

This insight comes from a fellow who, against all odds, survived his jump off the Golden Gate Bridge on September 25, 2000. Kevin Hines was 19, had been diagnosed with mental illness, had long contemplated ending his life, and should have been killed on impact. Almost no one survives jumping off the Golden Gate Bridge. It is one of the most lethal suicide strategies in America. Since the bridge opened in 1937, over 1,600 bodies have been retrieved. The survival rate is estimated to be 2 percent.

Kevin climbed over the railing, leaned back, let go, and felt, he says, “instant regret, powerful, overwhelming. As I fell, all I wanted to do was reach back to the rail, but it was gone.”

He plummetted 220 feet in four seconds, going 75 miles per hour and wracked by the thought all the way down: What have I just done? I don’t want to die. God, please save me.

He hit the water in a seated position and broke his back, shattering his T12, L1, and L2 vertebrae upon impact. Disoriented under the water, in agonizing pain, he was suddenly desperate to live. He flailed to get back to the surface, telling himself, Kevin, you can’t die here. If you die here, no one will ever know that you didn’t want to.

Kevin was rescued by the Coast Guard. Now he tells as many people as possible about watching his hands release their grip on the railing and the instant devastation he felt. He wants everyone to know that the act of suicide leads not to a final sense of satisfaction and relief but to panic-stricken sorrow.

And why did this help me?

Sol was furious and depressed and demoralized and ashamed and disappointed and drunk. But I’m certain he didn’t really mean to throw his life away. After reading about Kevin Hines, I came to believe that Sol’s last moment of consciousness might have been something like: “Wait — no!!” His rope skills meant that he’d woven a perfect noose, so there would be no escape for him. But I believe it flashed across his mind that he’d just made a monumentally stupid mistake. I believe, at the very end, he was turning back toward us, reaching back for his beautiful life.

Melissa Fay Greene is an American nonfiction author. A 1975 graduate of Oberlin College, Greene is the author of six books of nonfiction, a two-time National Book Award finalist, and a 2011 inductee into the Georgia Writers Hall of Fame. Greene has written for The New Yorker, The New York Times, The Washington Post, New York Magazine, Newsweek, Life Magazine, Good Housekeeping, The Atlantic, Readers Digest, The Wilson Quarterly, Redbook, MS Magazine, CNN.com and Salon.com.