Yesterday would have been Zack’s 40th birthday. He took his own life last year after a twenty year struggle with schizophrenia. I loved Zack, the son of a first cousin who has been like a brother to me. Zack and I first met at his bris, the Jewish circumcision ritual, when he was only a couple of days old and I had just started my first “real” job. I was apprehensive about missing work  my first week, but had an understanding boss. I went to work first, then drove to Brooklyn in my suit and tie. Zack was born into a family of genuine, certified hippies, and I felt like such an outsider, but was warmly welcomed. He was a gorgeous baby, and matured into a fine young man. When he graduated from one of Brooklyn’s best prep schools he was among the top five in his class, and beloved by his peers. The summer before going off to college he interned in a department I ran at NYU Medical Center, and was adored by my colleagues.

my first week, but had an understanding boss. I went to work first, then drove to Brooklyn in my suit and tie. Zack was born into a family of genuine, certified hippies, and I felt like such an outsider, but was warmly welcomed. He was a gorgeous baby, and matured into a fine young man. When he graduated from one of Brooklyn’s best prep schools he was among the top five in his class, and beloved by his peers. The summer before going off to college he interned in a department I ran at NYU Medical Center, and was adored by my colleagues.

A few months later in mid-November my first wife, Vanessa, succumbed to cancer. Zack was very attached to her, and had come down from college to visit her during her final weeks in the hospital. Four months after her death Zack called me from his dorm room. He was talking strangely about knives and sexual abuse, and paranoid fantasies. He was adamantly anti-drug and consumed little alcohol, and I knew enough to know this sounded like something else. I tracked down his dad who went right to his college and brought him home. He was hospitalized, and we eventually got the diagnosis of schizophrenia, which often manifests in late adolescence. To shorten this story, it was downhill from there–hospitalizations, group homes, religious delusions, medication non-compliance. He was, to the end, the gentlest of people, and never hurt anyone or broke any laws. He lived a simple life free of challenges, but was tortured by his disease until, after several earlier attempts, succeeded in taking his own life.

I grieved for Zack for nearly twenty years before he died. What we had all lost was the potential Zack, that wonderful, bright child who never got to grow up to be an educator or social worker, or whatever he wanted to be. That Zack died with the schizophrenia diagnosis and the severity of the disease. When he finally passed, I hardly mourned because of my anticipation of its inevitability.

Forty is a powerful number. When I turned forty, it was seven months after my wife’s first diagnosis of cancer. During surgery for routine uterine fibroids, the surgeons came out to tell me they had been wrong; she had a form of colon sarcoma, and they would be performing a hysterectomy and bowel resection. I went to a friend’s medical office and learned that the two-year survival rate was almost zero. Later, in the elevator taking her up to her room two residents were discussing her case unaware of my presence. One conjectured that she would be dead in six months. She wasn’t. During the months of the worst kind of chemotherapy she almost died twice from sepsis, more common in those days than now. She beat the odds and we lived well for five years before a more resistant strain would not be cowed by chemotherapy.

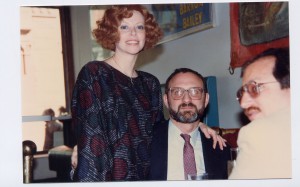

What does this have to do with forty? She was in the hospital fighting sepsis for ten days, emerging two days before my fortieth  birthday. She told me we had tickets to a Broadway show–I can’t remember which–but had to stop at my cousin’s restaurant to pick up a package he had left for me. I walked into the surprise party of life. She had organized the whole thing from inside her sterile tent in a hospital bed. I had spent seven months grieving for the loss of what was to be for us, a future we had envisioned that included a child and growing old together. During the next four years, we crammed everything we could into life, both knowing how tenuous our grasp on life together could be. When she finally died, after nine weeks of in the hospital with everything going wrong that could, I felt grieved out. I had spent so much time pre-grieving that the final rituals of laying her to rest were almost a relief. When I started dating, everyone thought it was ‘too soon,’ but my clock was different from theirs.

birthday. She told me we had tickets to a Broadway show–I can’t remember which–but had to stop at my cousin’s restaurant to pick up a package he had left for me. I walked into the surprise party of life. She had organized the whole thing from inside her sterile tent in a hospital bed. I had spent seven months grieving for the loss of what was to be for us, a future we had envisioned that included a child and growing old together. During the next four years, we crammed everything we could into life, both knowing how tenuous our grasp on life together could be. When she finally died, after nine weeks of in the hospital with everything going wrong that could, I felt grieved out. I had spent so much time pre-grieving that the final rituals of laying her to rest were almost a relief. When I started dating, everyone thought it was ‘too soon,’ but my clock was different from theirs.

Preparing for grief and loss seems inevitable and is common and natural. I saw it early in my career when I worked with parents of severely handicapped children. Parents mourned the loss of the child they expected to raise to adulthood, children that would someday bury them, and not the other way around. I’ve seen it more recently in the families of Alzheimer’s victims where the soul they loved so dearly died years before they body gave out. It is not something to be ashamed of, those inevitable thoughts. They are representative of the great love you felt for what could have been. It is a form of self-therapy, not betrayal. Learn to live with pre-grieving, and embrace it.

Be well.

Great article.