Denial makes things a blur. I know that I plunged myself to those depths of unfeeling because I wanted to survive, and on good days, I can forgive myself for it. I must have been there for over a year, when I could smell a musty, old dream of college – long forgotten in the pain of my father’s death. Sure, I could bury my head in a textbook and pretend that’s what got me through the grieving, but most people who have lost a loved one can understand that there is no life after the loss, at least not for a while. It felt like there was a zombie apocalypse after my Dad’s funeral. I went from day to day, shell shocked, with my entire world destroyed. You cannot have the same dreams you used to when that kind of pain enters your existence.

Denial makes things a blur. I know that I plunged myself to those depths of unfeeling because I wanted to survive, and on good days, I can forgive myself for it. I must have been there for over a year, when I could smell a musty, old dream of college – long forgotten in the pain of my father’s death. Sure, I could bury my head in a textbook and pretend that’s what got me through the grieving, but most people who have lost a loved one can understand that there is no life after the loss, at least not for a while. It felt like there was a zombie apocalypse after my Dad’s funeral. I went from day to day, shell shocked, with my entire world destroyed. You cannot have the same dreams you used to when that kind of pain enters your existence.

As I said, over a year later there was some form of emotional awakening. I think what really inspired me was my mother. I remember in the beginning, my Mom would lay in bed all day unable to speak. This was the worst time  for me, because I really thought I had lost both parents, and it ripped me apart. A world without my dad was bad enough, but I needed my mom. Somehow, through the unfathomable pain of having to walk her lifelong partner through his death and the grieving process, my mom knew that. She knew that my sister and I needed her, and within a matter of weeks she had bounced back. She smiled and laughed again, she took care of us, and she became the rock of the family. I think that, in the least dramatic way possible, one day I saw her achievement for what it was. I decided that my family needed me, and that I wanted to feel again.

for me, because I really thought I had lost both parents, and it ripped me apart. A world without my dad was bad enough, but I needed my mom. Somehow, through the unfathomable pain of having to walk her lifelong partner through his death and the grieving process, my mom knew that. She knew that my sister and I needed her, and within a matter of weeks she had bounced back. She smiled and laughed again, she took care of us, and she became the rock of the family. I think that, in the least dramatic way possible, one day I saw her achievement for what it was. I decided that my family needed me, and that I wanted to feel again.

The extensive emotional breakdowns that were required to tear down my psychological barriers are times that I do not care to detail right now. It took a while, but I can finally say that I am a sentient being again – for the most part. What is scary about coming out of denial is looking back on those blurry memories and understanding that the girl in them is myself.

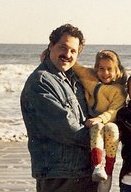

My first AfterTalk post was about telling my sob story, and how I am rather efficient at it. Just because I can tell it does not mean I can feel it. Ninety percent of the time I phone it in, and ten percent of the time it shocks me. I think about walking on  the beach with my dad, and him telling me his diagnosis while I berated him with requests for details on chemotherapy. I think about a 15 year old girl who stayed in the apartment by herself until eleven every night, with friendly neighbors delivering food for every meal of the day. I think about a girl who was able to go to Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center at the end, and tell her drugged up father that he was her hero, albeit through violent sobs and wads of tissue. I cannot identify with this girl.

the beach with my dad, and him telling me his diagnosis while I berated him with requests for details on chemotherapy. I think about a 15 year old girl who stayed in the apartment by herself until eleven every night, with friendly neighbors delivering food for every meal of the day. I think about a girl who was able to go to Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center at the end, and tell her drugged up father that he was her hero, albeit through violent sobs and wads of tissue. I cannot identify with this girl.

Sometimes I think this is why I don’t maintain a lot of friendships from high school. The girl who went back to a cutthroat environment after three days of Shiva is a stranger to me. However, there is a thought that scares me more. Sometimes, when I think back on a little Caitlin with banana curls, with a healthy, loving father, and she is a stranger too.